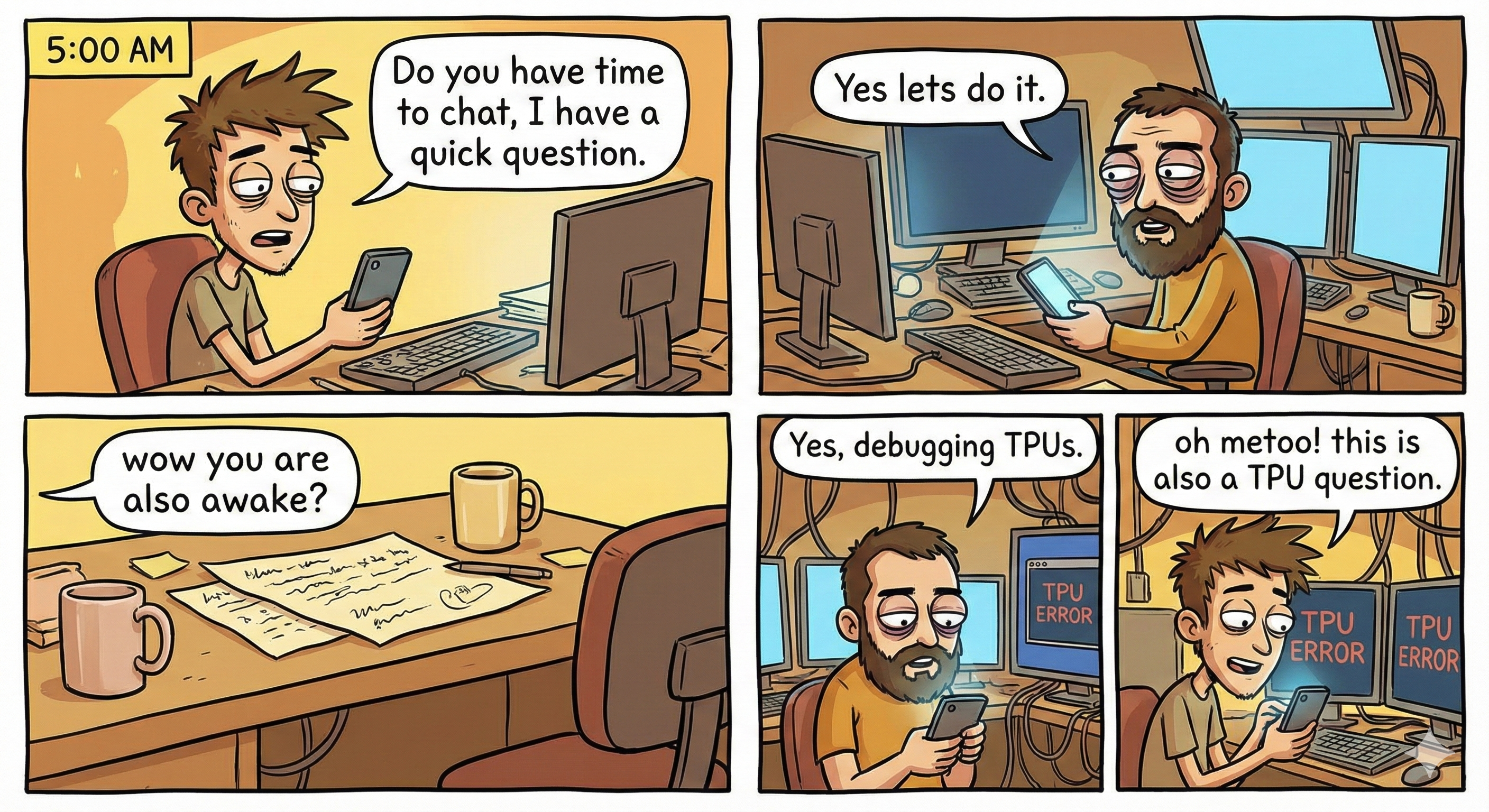

Training large foundation models in academia presents a unique set of challenges. Unlike industry labs with dedicated infrastructure teams and infinite compute, academic research often requires us to be our own DevOps engineers, kernel optimizers, and distributed systems architects.

Over the past two years, we've spent thousands of hours debugging, profiling, and optimizing training runs on TPUs (v3 through v6e). This post distills the hard-earned lessons from that journey.

Why TPUs?

With the recent developments in Generative AI (LLMs, diffusion models, etc.), it is getting more and more expensive to do impactful research. Training state-of-the-art models often requires massive amounts of compute, but in academia, most students simply cannot access that scale of hardware.

However, we still want to do good research and train large models. This is where the TPU Research Cloud (TRC) program comes in. We want to sincerely thank TRC for sponsoring free Cloud TPUs, which has empowered us and many other students to tackle ambitious research problems that would otherwise be impossible.

Why TorchXLA?

When we first got access to TPUs, a natural question arose: should we rewrite everything in JAX?

The answer, for us, was a pragmatic no. We're almost always building on top of existing work. The model architectures we wanted to study, the training recipes we wanted to adapt, the community codebases we wanted to extend—nearly all of them were written in PyTorch. Rewriting a complex codebase from scratch in a new framework is a months-long endeavor with a high risk of introducing subtle bugs.

TorchXLA offered us the best of both worlds: the ability to keep our familiar PyTorch code while compiling it to run efficiently on TPU hardware via the XLA compiler.

Of course, the reality is more nuanced (as you'll see in the next section), but the barrier to entry is lower than a full framework migration. We could take a working LLaVA training script, make targeted modifications, and have it running on a TPU pod within weeks rather than months.

From Torch To TorchXLA: The Transition

Migrating a standard PyTorch training loop to run efficiently on TPUs isn't just a one-line change. It requires understanding how XLA compiles your graph.

Static Shape! Static Shape! Static Shape!

If there is one mantra to memorize before touching a TPU, it is this: Dynamic shapes are the enemy.

PyTorch allows us to pass tensors of varying sizes through our model, and CUDA kernels handle it gracefully. On TPUs, however, the execution model is different. The XLA compiler traces your computation graph and compiles it into a static executable.

Every time the input shape changes, XLA must recompile the entire graph. This recompilation can take minutes. If your batch size or sequence length changes every step, your training will spend 99% of its time compiling and 1% computing.

A Simple Example

Consider a simple function that processes a batch of sentences. In standard PyTorch, we might just pass the list of sentences directly.

# ❌ BAD: Dynamic Shapes

# If 'batch' has different lengths each time, XLA recompiles every step!

def forward(batch_of_tokens):

# shape: [B, dynamic_seq_len]

return model(batch_of_tokens)To fix this, we must ensure every tensor has a fixed, known size at compile time. This usually means padding everything to a maximum length.

# ✅ GOOD: Static Shapes

# Pad everything to a fixed max_length (e.g., 2048)

def forward(batch_of_tokens_padded):

# shape: [B, 2048] <- Always the same!

return model(batch_of_tokens_padded)A Real-World Example: The Cambrian Experience

When we started developing Cambrian-1, we adapted the LLaVA codebase to run on TPUs. Initially, training would start, but it was much slower than expected. We were seeing step times measured in minutes rather than seconds.

The demon hiding in the details was dynamic shapes.

In multimodal LLM training, data is naturally "ragged." One sample might be a text-only conversation (0 images). The next might describe a single photo (1 image). Another might compare three different charts (3 images).

In standard PyTorch/CUDA, you just loop through the images you have. But on TPU, this variation is catastrophic:

- Batch 1: Max 2 images → Shape

[B, 2, C, H, W]→ Compile! - Batch 2: Max 5 images → Shape

[B, 5, C, H, W]→ Recompile! - Batch 3: Text only → Shape

[B, 0]→ Recompile!

The XLA compiler was recompiling the training graph for nearly every single batch.

The Solution: Padding with Dummy Images

To fix this, we had to standardize the data shape at the dataloader level. We defined a fixed "max images" budget (e.g., 5 images per sample).

If a sample has fewer images, we pad it with dummy black images up to the max count. We then use a boolean mask to ensure the model ignores these dummy images during the forward pass.

# Simplified fix for static multimodal batches

MAX_IMAGES = 5

def collate_fn(batch):

# 1. Pad image tensors to [B, MAX_IMAGES, C, H, W]

# 2. Create an attention mask for valid images

padded_images = torch.zeros(batch_size, MAX_IMAGES, 3, 336, 336)

image_masks = torch.zeros(batch_size, MAX_IMAGES, dtype=torch.bool)

for i, sample in enumerate(batch):

n_imgs = len(sample['images'])

# Fill valid images

# Spoiler Alert: This kind of indexing operation will also fail in SPMD TorchXLA :(

padded_images[i, :n_imgs] = sample['images']

image_masks[i, :n_imgs] = True

# Remaining slots are zeros (dummy images)

return padded_images, image_masksOnce we implemented this, our step times dropped instantly from minutes to milliseconds. The graph compiled once, and the TPU could finally fly.

Gradient Checkpointing Compatibility

Another common pitfall when adapting existing codebases: gradient checkpointing.

Many PyTorch codebases use torch.utils.checkpoint.checkpoint for memory-efficient training.

However, this doesn't play well with TorchXLA's compilation model.

You need to replace it with the XLA-native version: torch_xla.utils.checkpoint.checkpoint.

Here's an example of monkey-patching a model's forward pass:

# Replace torch gradient checkpointing with XLA-compatible version

from torch_xla.utils.checkpoint import checkpoint as xla_checkpoint

def patched_forward(self, sample):

sample = self.conv_in(sample)

if self.training and self.gradient_checkpointing:

# Use XLA checkpoint instead of torch.utils.checkpoint

for down_block in self.down_blocks:

sample = xla_checkpoint(down_block, sample)

sample = xla_checkpoint(self.mid_block, sample)

else:

for down_block in self.down_blocks:

sample = down_block(sample)

sample = self.mid_block(sample)

sample = self.conv_norm_out(sample)

sample = self.conv_act(sample)

sample = self.conv_out(sample)

return sample

# Apply the patch

import types

model.encoder.forward = types.MethodType(patched_forward, model.encoder)

This pattern of "find-and-replace" for XLA compatibility is unfortunately common.

Grep your codebase for torch.utils.checkpoint and replace accordingly.

Scaled Dot-Product Attention (SDPA)

Another silent killer: F.scaled_dot_product_attention. This is the efficient fused attention

implementation introduced in PyTorch 2.0, and it's used extensively in modern pretrained models and libraries

like HuggingFace Diffusers.

The problem? It silently fails on TorchXLA. Your code will crash with no clear error message, leaving you debugging for hours. The fix is to replace SDPA with a manual attention implementation:

# ❌ BAD: F.scaled_dot_product_attention crashes on TPU

hidden_states = F.scaled_dot_product_attention(

query, key, value, attn_mask=attention_mask, dropout_p=0.0, is_causal=False

)

# ✅ GOOD: Manual attention implementation

import math

scale = 1.0 / math.sqrt(query.shape[-1])

attn_scores = torch.matmul(query * scale, key.transpose(-2, -1))

if attention_mask is not None:

attn_scores = attn_scores + attention_mask

attn_probs = attn_scores.softmax(dim=-1)

hidden_states = torch.matmul(attn_probs, value)

The tricky part is that SDPA is often buried deep inside library code. For example, when training

diffusion models with the Flux VAE, we had to monkey-patch the AttnProcessor2_0 class

from HuggingFace Diffusers:

# Monkey-patch Diffusers attention for XLA compatibility

if IS_XLA_AVAILABLE:

from diffusers.models.attention_processor import AttnProcessor2_0

import math

def xla_compatible_attention(self, attn, hidden_states,

encoder_hidden_states=None,

attention_mask=None, temb=None, *args, **kwargs):

# ... setup code ...

query = attn.to_q(hidden_states)

key = attn.to_k(encoder_hidden_states)

value = attn.to_v(encoder_hidden_states)

# Reshape for multi-head attention

query = query.view(batch_size, -1, attn.heads, head_dim).transpose(1, 2)

key = key.view(batch_size, -1, attn.heads, head_dim).transpose(1, 2)

value = value.view(batch_size, -1, attn.heads, head_dim).transpose(1, 2)

# Manual attention instead of F.scaled_dot_product_attention

scale = 1.0 / math.sqrt(query.shape[-1])

attn_scores = torch.matmul(query * scale, key.transpose(-2, -1))

if attention_mask is not None:

attn_scores = attn_scores + attention_mask

attn_probs = attn_scores.softmax(dim=-1)

hidden_states = torch.matmul(attn_probs, value)

# ... rest of forward pass ...

return hidden_states

AttnProcessor2_0.__call__ = xla_compatible_attentionscaled_dot_product_attention in both your code AND your dependencies (e.g., site-packages/diffusers/).

Distributed Training Strategies

As models grow larger, you'll quickly outgrow what fits on a single TPU chip. Here's the evolution of parallelism strategies we've used on TPUs, roughly in order of increasing complexity:

- DDP (Distributed Data Parallel): The starting point—replicate the model, shard the data.

- FSDP (Fully Sharded Data Parallel): Shard model parameters across devices to fit larger models.

- SPMD (Single Program Multiple Data): Fine-grained tensor-level sharding with explicit mesh control.

DDP

A typical starting point for distributed training is Distributed Data Parallel (DDP). As of 2025, TorchXLA supports DDP via xmp.spawn().

torch.nn.parallel.DistributedDataParallel has considerably worse performance on TPUs and is not fixed before TorchXLA 2.5, as far as we know. Use xmp.spawn() instead.

Mark Step: A major difference between TorchXLA and torch CUDA is the need to call xm.mark_step() at the end of each training step. This signals to the XLA compiler that the computation for this step is complete and allows it to optimize execution. Otherwise, the compiler will try to unroll the loop into a single giant graph (which could be millions of times larger than expected) and lead to infinite compiling time. Although many wrappers in FSDP/SPMD handle this internally, on DDP we have much less abstraction and everything is done manually, so forgetting to call xm.mark_step() can be a common pitfall.

FSDP

When your model no longer fits in memory on a single device, Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) becomes essential. FSDP shards model parameters, gradients, and optimizer states across devices, only gathering them when needed for computation.

If you're looking for a reference implementation, we highly recommend studying the

HuggingFace Transformers Trainer.

The _wrap_model method around line 1953 is an excellent starting point for understanding how FSDP wrapping is configured for TorchXLA.

The Trainer handles many edge cases and provides a battle-tested template for your own implementations.

In TorchXLA FSDP, each device first loads its own copy of the full model in fp32, and then applies sharding. Each TPU device typically has ~100GB of RAM. This means if your model exceeds roughly ~25-30B parameters, the codebase will crash with an OOM error before sharding even begins.

Workarounds we tried:

- Meta device initialization: Does not work with TorchXLA FSDP as of our testing.

- Loading in bf16: This works, but requires significant code changes in the TorchXLA library itself. See our Cambrian train_fsdp.py for a reference implementation.

SPMD

SPMD (Single Program Multiple Data) is Google's approach to distributed training, offering fine-grained control over how tensors are sharded across devices. In theory, it's the most efficient way to train on TPUs. In practice, it requires significant debugging.

Based on our experience, we never got arbitrary SPMD sharding to work well. By "work," we mean both efficiency and effectiveness—the code would run, but it didn't beat FSDP v1 in practice.

However! After months of debugging, we got FSDP via SPMD working. This hybrid approach uses SPMD's infrastructure with FSDP-style sharding semantics. Our Cambrian-S codebase is built on FSDP via SPMD, and it delivers real improvements in both speed and numerical precision (since SPMD allows higher precision training more easily).

But it comes with its own set of bugs. Here's what we've encountered:

Bug #1: The Indexing Problem

Indexing is fundamental to AI coding. Operations like a[b] = c are everywhere—inserting image tokens

into text sequences, gathering embeddings, scatter operations. In TorchXLA SPMD, this triggers an implicit

all_gather.

When your tensors a, b, and c become large, the code crashes immediately

with an OOM error. You've just lost all the benefits of sharding.

embeddings[indices] = values

trigger implicit all-gathers in SPMD, causing OOM crashes on large tensors. This silently defeats the purpose of sharding.

The Fix: We had to write custom scatter kernels that explicitly handle the sharding. This involves manually enabling/disabling sharding around the operation:

import torch_xla.distributed.spmd as xs

class CustomScatterKernel(torch.autograd.Function):

"""Custom kernel to avoid implicit all_gather in SPMD indexing."""

@staticmethod

def forward(ctx, input_embeds, img_embeds, token_indices):

ctx.full_input_shape = input_embeds.shape

ctx.full_img_shape = img_embeds.shape

ctx.dtype = input_embeds.dtype

# Manually handle sharding to avoid implicit all_gather

sharded_input = xs.enable_manual_sharding(

input_embeds, ("fsdp", None, None)).global_tensor

sharded_img = xs.enable_manual_sharding(

img_embeds, ("fsdp", None, None)).global_tensor

sharded_indices = xs.enable_manual_sharding(

token_indices, ("fsdp", None)).global_tensor

# Concatenate and gather on sharded tensors

sharded_embeds = torch.cat([sharded_input, sharded_img], dim=1)

sharded_embeds = torch.gather(

sharded_embeds, 1,

sharded_indices.unsqueeze(-1).expand(-1, -1, sharded_embeds.size(-1))

)

# Restore automatic sharding

output = xs.disable_manual_sharding(

sharded_embeds, ("fsdp", None, None),

input_embeds.shape, mesh=xs.get_global_mesh()

).global_tensor

ctx.save_for_backward(token_indices)

return output

@staticmethod

def backward(ctx, grad_output):

# Similar manual sharding logic for backward pass

token_indices, = ctx.saved_tensors

# ... scatter_add with manual sharding ...

return grad_input, grad_img, NoneYou then carefully prepare your embeddings (remember: static shapes!) and use the custom kernel:

# Instead of: input_embeds[vision_token_indices] = image_features ❌

# Use the custom kernel:

input_embeds = CustomScatterKernel.apply(

input_embeds, image_features, vision_token_indices

) # ✅The logic is complicated, but the pattern is: wrap indexing operations with manual sharding control to prevent the XLA compiler from inserting expensive all-gathers.

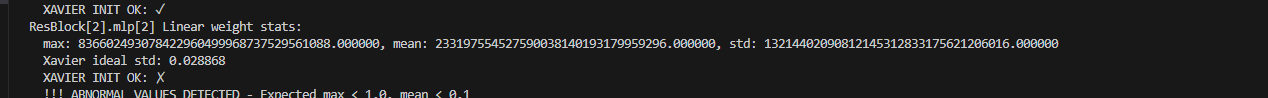

Bug #2: The Initialization Problem

PyTorch's nn.init.* functions (like xavier_uniform_, normal_, etc.)

sometimes produce unexpected results on TorchXLA. We've seen cases where initialization

produces values that are orders of magnitude off from expected. If your training immediately produces

NaN losses, diverges within the first few steps, or your initial loss value is astronomically large—this

initialization bug is likely the culprit.

The Fix: Write manual initialization functions that explicitly control the random number generation and tensor operations. We maintain separate initialization paths for GPU vs TPU:

if IS_XLA_AVAILABLE:

self.initialize_weights_tpu() # Manual TPU-friendly init

else:

self.initialize_weights_gpu() # Standard nn.init.* callsThe TPU-friendly version manually implements each initialization:

@torch.no_grad()

def manual_xavier_uniform(tensor):

"""TPU-friendly xavier_uniform_ implementation."""

fan_in, fan_out = nn.init._calculate_fan_in_and_fan_out(tensor)

bound = math.sqrt(6.0 / (fan_in + fan_out))

# Generate uniform values and scale to [-bound, bound]

random_tensor = torch.empty_like(tensor, dtype=torch.float32).uniform_(0, 1)

random_tensor = random_tensor * (2 * bound) - bound

# Use copy_ for reliable TPU behavior

tensor.data.copy_(random_tensor.to(tensor.dtype))

return tensor

@torch.no_grad()

def manual_normal_(tensor, mean=0.0, std=1.0):

"""TPU-friendly normal_ implementation."""

normal_tensor = torch.zeros_like(tensor, dtype=torch.float32)

normal_tensor.normal_(mean=mean, std=std)

tensor.data.copy_(normal_tensor.to(tensor.dtype))

return tensor

You then apply these manual functions instead of the standard nn.init.* calls,

with xm.mark_step() calls between initialization phases to force synchronization:

def initialize_weights_tpu(self):

"""Robust TPU-friendly initialization."""

# Initialize linear layers with manual xavier

for name, module in self.named_modules():

if isinstance(module, nn.Linear):

manual_xavier_uniform(module.weight)

if module.bias is not None:

module.bias.data.fill_(0.0)

# Force synchronization after each phase

xm.mark_step()

# Zero-init specific layers (e.g., adaLN modulation)

for block in self.transformer_blocks:

block.adaLN_modulation[-1].weight.data.fill_(0.0)

block.adaLN_modulation[-1].bias.data.fill_(0.0)

xm.mark_step()

# Validate initialization

self._check_weight_statistics()Bug #3: The Compiler Gets It Wrong

Sometimes you've written everything correctly—static shapes, no implicit all-gathers, proper initialization—but you still get unexpected OOM errors. In these cases, the XLA compiler itself may be making incorrect sharding decisions.

The SPMD compiler tries to infer optimal sharding for intermediate tensors, but it doesn't always get it right. A tensor that should stay sharded might get unexpectedly replicated, causing memory to explode.

The Fix: Manually remind the compiler how tensors should be sharded using xs.mark_sharding():

# When the compiler makes wrong sharding decisions,

# explicitly mark how tensors should be sharded

import torch_xla.distributed.spmd as xs

# After operations that might confuse the compiler

xs.mark_sharding(tensor, xs.get_global_mesh(), ("fsdp", None))

# Example in practice:

def forward(self, x):

# ... some computation ...

output = self.layer(x)

# Remind compiler this should stay sharded on first dim

xs.mark_sharding(output, xs.get_global_mesh(), ("fsdp", None))

return output

This is essentially "hinting" to the compiler: "I know what I'm doing—keep this tensor sharded this way."

It's frustrating to debug, but sprinkling mark_sharding calls at strategic points can

turn an OOM crash into a working training run.

Can LLMs Write TPU Code?

For many researchers, "vibe-coding" or LLM-assisted coding has become a de-facto practice when starting new projects. But do LLMs actually understand the nuances of TPU and TorchXLA development? Over the past two years, especially with the introduction of reasoning models, our experience has been a mix of impressive capabilities and frustrating hallucinations.

What Works Well

- Infrastructure Management: LLMs have mastered most TPU CLI commands. Since many TRC TPUs are preemptible, having LLMs write scripts to create, inspect, and auto-restart TPUs is a huge time-saver.

What Breaks & How to Fix It

-

Outdated TPU APIs. TPU commands change frequently. LLMs are often stuck on older versions, leading to code that is either deprecated or pure hallucination.

Fix: When prompting, explicitly paste the latest API documentation (or web link) or error logs. -

TorchXLA Codes. TorchXLA looks deceptively similar to standard PyTorch. LLMs often default to writing standard PyTorch code (like using `.cuda()` or code with dynamic shapes) that is catastrophic for XLA performance.

TorchXLA APIs also change quite frequently, so LLMs generation can be full of hallucinations. Overall this makes TorchXLA codes very fragile and hard to maintain with LLMs.

Fix: Unfortunately there is no good way to fix this. On the bright side, we have been (forced) to learn about the fundamentals of many code, like sharding, model resuming, etc. This is a motivation to learn more about the fundamentals of the code. Some tips that might help: try using the best model, turn the max reasoning and tell the model explicitly this is TPU codee, TorchXLA code, please reason your best instead of relying on pre-existing knowledge.

The Data Bottleneck

In academic clusters, we often take shared filesystems (NFS/GPFS) for granted. On Cloud TPUs, storage requires more deliberate planning. We primarily rely on two options: Google Cloud Storage (Buckets) and Persistent Disks (PD).

Persistent Disks (PD): The "Normal" Filesystem

Persistent Disks behave like a standard filesystem. They are reliable and less prone to random failures compared to network mounts. However, they come with significant caveats, especially when moving between TPU generations:

- Cost on v6: While normal PDs work well on v4 pods. On v5 pods, only balanced PD (2x expensive than normal PDs) is allowed, and only allowed to be attached to a single pod or a maximum of 10 TPU VMs. On v6 pods, only hyperdisk ML Disks (4x expensive than normal PDs) are allowed and shares the same attachment limitation as v5 pods.

- The Read-Write vs. Parallelism Conflict: On a parallel TPU pod (e.g., v4-256), disks must be mounted in read-only mode to be attached to multiple VMs simultaneously. Read-Write access is restricted to a single VM (like a v4-8). This means it is impossible to save checkpoints or logs back to the disk during a large distributed run.

- Mutual Exclusion: A disk cannot be mounted as Read-Only and Read-Write simultaneously. This means you cannot "hot-fix" your code or update your dataset on the disk while a training run is reading from it.

The "Clone & Scale" Workflow

To navigate the PD limitations, we adopted a staged workflow that separates development from production training.

- Develop on -8: We maintain a small TPU node (e.g., v4-8) with a Read-Write disk. This is our "dev box" where we write code, debug, and cook data.

- Snapshot & Clone: Once the code and data are ready, we create a disk snapshot/clone.

- Train on Pod: We mount this cloned disk as Read-Only on the large training pod (e.g., v4-256). This ensures data consistency and allows the large pod to scale without lock contention.

- Iterate: If we need to change the data, we go back to step 1, modify the RW disk, and create a new clone for the next run.

Google Cloud Storage (Buckets)

Google Cloud Storage (GCS) Buckets offer a flexible alternative to Persistent Disks. They provide virtually unlimited cloud storage and can be accessed concurrently by multiple TPU VMs without the read-write restrictions of PDs.

gcsfuse. This allows seamless read and write access across all VMs in a pod without the need for writing GCS-dependent read and write code.

GCSFuse provides multi-level of consistency by introducing a `ttl-secs` parameter that controls how long file metadata and directory listings are cached. Setting this parameter to 0 ensures the strongest consistency, where all read and write operations reflect the most recent changes. But this may introduce latency overhead and large amount of cost due to frequent metadata operations. For training workloads where data is mostly read-only, a higher `ttl-secs` (e.g., 60 seconds) can be used to improve performance and reduce costs, while still maintaining reasonable consistency.

Conclusion

Despite the initial friction, mastering the TPU stack has allowed us to train models like Cambrian-1, Cambrian-S, RAE, and scaled-RAE at scale. The ecosystem is maturing, and we hope this post helps you avoid some of the pitfalls we encountered.

If you have comments, suggestions, or want to share your own TPU debugging war stories, please reach out to Shengbang Tong or Boyang Zheng.

Citation

Please cite this work as: